A collaboration with the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire sheds light on Black history at this Hancock reservation

- Tags:

- Forest Society History

By Eric Aldrich

At the Forest Society’s Welch Family Farm and Forest in Hancock, there’s a boulder where the Welch family’s home once stood. The south side of the boulder holds a plaque commemorating three generations of the Welch family at the site between 1862 and 2000, when Elizabeth C. Welch donated the land to the Forest Society.

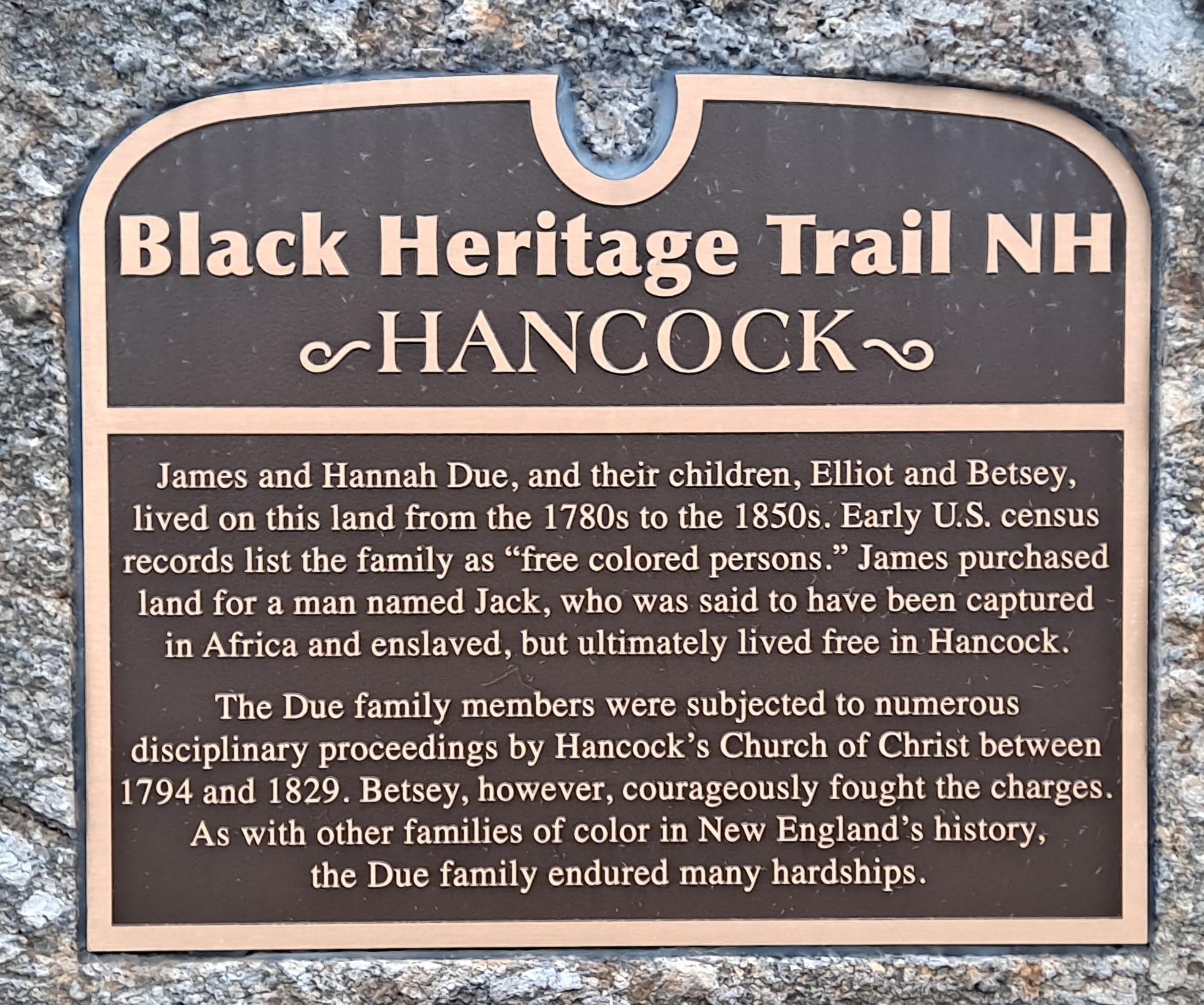

On the north side of the boulder there’s a new plaque that commemorates those who lived there before the Welches: James and Hannah Due and their friend Jack, a former enslaved man who lived free in Hancock. The new plaque, installed in September by the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire, sheds light on a side of history that has too long been in the shadows in New Hampshire and beyond.

Since acquiring the property in 2000, the Forest Society has known about the Welch family’s legacy on the land. The Welches were pioneers of a movement among New Hampshire farmers between the late-1800s and mid-1900s to board city-dwelling summer visitors to the country to supplement their farming income. Older residents of Hancock remember the Welch’s visitors, their fresh food off the farm, and their warm hospitality. But until recently, the Forest Society—and many other folks in Hancock—knew nothing about the Welch’s predecessors, the Due family and Jack.

“Do you know about the land’s Black history?”

I learned about the Dues and Jack sometime in the 1990s; I can’t remember exactly when. I had been hunting near my home in the southwestern part of town—miles away from the Welch farm—when I came across a cellar hole, the old stone foundation of a home. Dogged by my obsession of cellar holes and wanting to know who lived where and when, I started digging into the records. Turns out, the cellar hole I had found was once topped by the home of Elliot Due, James and Hannah Due’s son. I learned that early census records indicated that the Dues were “free colored people.” More fascinated, I dug further, encouraged by tips from local historians and by JerriAnne Boggis, who would later become executive director of the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire.

One clue led to another, while many questions have remained unanswered. I found that Elliot was born and raised at his parents’ home on the old road between Hancock and Stoddard, now the Forest Society’s Welch Family Farm and Forest. Aside from the boulder marking the house site and the open fields that continue to grace this pleasant location, there’s little sign of the land’s early occupants.

In 2010, some 10 years after the Forest Society acquired the property, I wasn’t sure whether they knew about the Due family and Jack. So, I sat down with Jack Savage, then the Forest Society’s vice president of communications, and Dave Anderson, director of education, and I asked them if they knew about the land’s Black history. They shook their heads. So, I told them the story— at least my understanding of it.

What little we know about the Due family and Jack comes from a few scant sources. It’s in bits and pieces from an 1889 history of Hancock, records from the church and town, registries of deeds and probate, U.S. censuses, and genealogists, such as the intrepid Pearl Louise Stimson, who spent years researching her own ancestry. Like so much of New England’s Black history, many details about the family are lost altogether.

James Due and “Old Jack”

We don’t know precisely when James Due came to Hancock, or where he came from, but we do know he was living in Hancock in 1779, the year of the town's incorporation. Census records from 1790 and 1800 indicate that James Due and those in his household were “free colored people.”

Closely associated with James Due and his family was a gentleman named Jack. Jack was reportedly born in Africa, captured and enslaved as a child, and brought over to this continent in what must have been a harrowing journey by ship. Somehow Jack became free and ended up in Hancock, living off and on with James Due and his family, possibly arriving with James when Jack was in his late 40s.

Also known as Jack Ware or “Old Jack” or “Old Negro Jack,” Jack worked with James Due for years, and James was interested in Jack’s well-being. In 1791 (when George Washington was president), James gave 70 acres to the town of Hancock to provide for Jack’s support. When not living with the Due family in the early 1800s, Jack lived in Peter Warren’s former home in the remote southwestern part of town, a quarter mile from what was then known as Warren Pond.

When Jack died in 1826, at the age of about 100, he was buried at Hancock’s Pine Ridge Cemetery, beside the Due family, with an inscription on his stone: “This monument erected in commemoration of his virtues, by the voluntary contributions of the Citizens of Hancock.”

Years later, Warren Pond became known as Jack’s Pond, and the place where Jack lived is now owned by the Harris Center for Conservation Education.

Gossip and Church Discipline

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, James and Hannah Due were raising two children and trying to eke out a living as farmers on their place on the old road to Stoddard. Their daughter, Betsey, married Richard Razey in 1808. They moved into a home barely half a mile from her parents. Betsey’s brother, Elliot, married Lois French in 1817, and they lived about a mile away near Hunts Pond.

Meanwhile, in the village of Hancock, the Church of Christ was one of the town’s dominant social forces. Led by its first two pastors, reverends Reed Paige and Archibald Burgess, the church leaned toward a strict form of Calvinism and leveled disciplinary actions against various members for charges such as neglecting public worship, deception, stealing, lying, intemperance, profanity, and adultery.

By 1841, Rev. Burgess’s attention was angrily focused on his church’s anti-slavery activists, who had attended a sermon given by Rev. Henry C. Wright, a prominent abolitionist who traveled throughout New England. Those members, too, were excommunicated from the church. A year later, a larger anti-slavery convention was held in town, whose speakers included an all-star lineup of fiery, traveling abolitionists. An anti-slavery newspaper at the time described local antagonists of the event as living “under the bloated tyranny of Archibald Burgess and a subaltern aristocracy.”

Life went on for the Due and Razey families. Their children grew up in Hancock, became adults, married, had children and grandchildren of their own, and moved to neighboring towns and beyond. A few family members fought in the Civil War, while others carried on the essential tasks of raising families, or became engineers or teachers. In recent years, a few descendants have discovered their ancestry and some surprises in the process. One, Abigail Atwood Ladd, even had the honor of unveiling the new plaque in Hancock.

New Light to a Chapter in One Place

Today, when you stand where the Dues and Welches once lived, you see a magnificent view of Skatutakee Mountain. The property is a sweet, quiet place. There’s little sign of the love and toil that the site’s inhabitants put into the land. You can only imagine the moments there: the births, marriages, and deaths. Crops planted, tended, and harvested. Moments of frustration and moments of tenderness.

The boulder where the house once stood doesn’t spell out these details. But it marks a chapter in one family’s presence here, along with that of their friend, Jack. And as Black lives have been too long in the shadows of history, the boulder and the new plaque bring light to one chapter in one special place.

- To support the Forest Society's stewardship efforts for the Welch and Due family marker and interpretation, please donate here.

Eric Aldrich is a writer who lives in Hancock. This article originally appeared in the Fall 2021 edition of Forest Notes magazine.