John Glessner, his wife Frances, and their children, George and Fanny, began visiting New Hampshire's North Country in 1878, seeking refuge in the clean mountain air for George's hay fever during the summer months.

In 1882 Glessner, purchased a 100-acre farm from Oren Streeter for $2,300. He had the Big House, the family's summer residence, constructed in the Queen Anne Style of architecture in 1883. Designed by Isaac Elwood Scott, the 19-room mansion was situated high on a hill, with spectacular views of the White Mountains. Over the years, the Glessners constructed various buildings, built elaborate gardens (including a formal garden designed by Frederick Law Olmsted's company), and added land to their Rocks.

The family would travel each summer via train from Chicago, with several servants preceding them to prepare the property for the Glessners' arrival. The Rocks boasted a windmill, green house, bee house, observatory, sawmill/pigpen, and many other structures. Although the Big House and other residences at The Rocks were removed in the late 1940s, many of the property's original buildings have been restored and are in use today. The Rocks is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Carriage Barn built in 1884, housed horses, cattle, and equipment for over a century. From 2023 to 2024, the barn was thoughtfully renovated to honor its history and create a center for conservation, collaboration, education, and forest exploration for the 21st century.

More on the Glessners and the Forest Society: People & Place

John Jacob Glessner joined the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests in 1903. John, his wife Frances and children George and Fanny began visiting the White Mountains from Chicago in the 1870s, drawn to the region for its reputation as a pollen-free environment for George, who suffered from acute hay fever. They purchased 100 acres in the shadow of Garnet Mountain, the Oren Streeter Farm in Bethlehem, and began building a summer retreat and working farm on the site in 1884.

Elsewhere in the White Mountains at that time, the Connecticut-based New Hampshire Land Company was pushing out farmers and innkeepers, buying up hill farms to resell in consolidated 10,000-acre blocks to large timber companies. By 1889, a state Forest Commission report warned that deforestation in the White Mountains was having a direct negative impact on the 1,100 summer inns and hotels in the region – and the $5 million in annual tourism spending they supported. In 1896, the management of the Amoskeg Manufacturing Company in Manchester blamed deforestation in the White Mountains for two years of flooding that pushed so much sediment into the Merrimack River that it forced the shutdown of the Amoskeg Mill, placing 6,000 people out of work.

By the end of his second term, Governor Frank West Rollins was calling for the state to buy the White Mountains – but instead, soon after leaving office, Rollins convened a small meeting on February 6, 1901 that became the formation of a citizens advocacy group, named that day as the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests. One of the new group’s founding campaigns was for the passage of the 1911 Weeks Act to extend the National Forest System to the east, and then later for the purchase of 6,000 acres in Franconia Notch for $400,000 – known then as “Little Yosemite.”

As the Forest Society grew, so did the Glessner landholdings – eventually reaching nearly 2,000 acres in total. Guided by Chicago architects Isaac Scott and Hermann von Holst, and the Boston-based Olmsted Company, The Rocks became known for its elegant and yet whimsical and pragmatic architecture, formal gardens and terraces. The result was a unique combination of working farm and gilded age summer retreat, ultimately including more than twenty structures and employing 100 people. In 1902, John Jacob Glessner was elected vice president of combined companies that became International Harvester. Still, he spent intervals during the summer at The Rocks, where the rest of his family and staff were in residence from June through September. Frances created an apiary, stamping her honey jars with an ornate Glessner G.

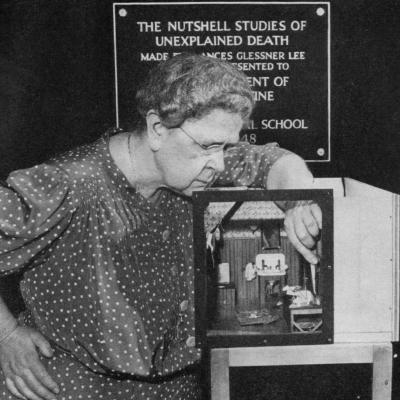

Both Glessner children, George and Fanny, became deeply attached to The Rocks. George settled permanently at his house, The Ledge, in 1916 and served 4 terms as a state representative. Fanny settled later at The Rocks, in 1938 after George’s death and the demise of her marriage to Blewitt Lee. It was at The Rocks that Fanny followed her calling: the study of forensic science and the creation of miniature crime scene dioramas, known as The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death – the original CSI.

Over a century of Glessner stewardship, the landscape changed significantly. Forests that had been cleared returned to the hillsides and buildings were raised, razed, and sometimes converted. In 1978, Fanny’s surviving children, John Glessner Lee and Martha Lee Batchelder, donated the property to the Forest Society for its permanent conservation, ultimately including about 1,400 acres and numerous buildings. The Forest Society operated The Rocks as a working Christmas tree farm and North Country Education Center, headquartered in the unique and massive “Tool Building” until it succumbed to fire in 2019.

Given the central role of the White Mountains to the very existence of the Forest Society, a northern hub located just minutes from Franconia Notch, with a view spanning the Kilkenny and the Presidentials is especially fitting. And given the importance of the ecology and economy of the Northern Forest to our shared well-being, from its carbon sequestration to outdoor recreation to sustainable forest products, the greater North Country is also central to our shared future.

Read more in the Autumn 2020 issue of Forest Notes about the property's history under the ownership of the Glessners.

The Glessners in Bethlehem

According to the Bethlehem Historical Society, John Glessner was involved in forming the Bethlehem Electric Light Co. in 1895:

"Up until 1896, Bethlehem streets were lighted by kerosene street lamps. There were about sixty lamps that had to be lighted individually each night during the summer season. Old records show that during the years from 1890 to 1893, James Eudy was lamp lighter, while in 1894, Allie Varney held this job. They were paid from $18.00 to $25.00 a month for their services.

In 1895, five men from Berlin and Gorham formed the Bethlehem Electric Light Co. and hired George H. Turner as manager. They built a wooden penstock from a mill dam and put in the first generator. The houses were wired and the charge was $3.00 per year per light and folks could burn all the electricity they liked. The current was on from dusk to midnight. Later, many improvements were made with the building of a new penstock and power house, and in 1896, street lights were added to take the place of the old kerosene lamps and all night service of lighting began. Meters were installed in the houses and in 1908, James Turner was hired to read the meters. About 1916, one of the owners and owner of most of the stock in the Electric Co., died. A man from Newton, Mass., bought out his interest and took over the operation of the Company. He ran it into bankruptcy and through the efforts of Mr. Turner, Mr. Glessner became interested and was appointed Receiver by the Court to run the business.

Mr. Glessner invested a lot of money in the company and gained the majority of stock. He had plans of forming a new company but died before this was accomplished. The Public Service Co. then bought out the old company and paid up all the minor stockholders and the Glessner Estate all the money Mr. Glessner had invested."