Nature's View

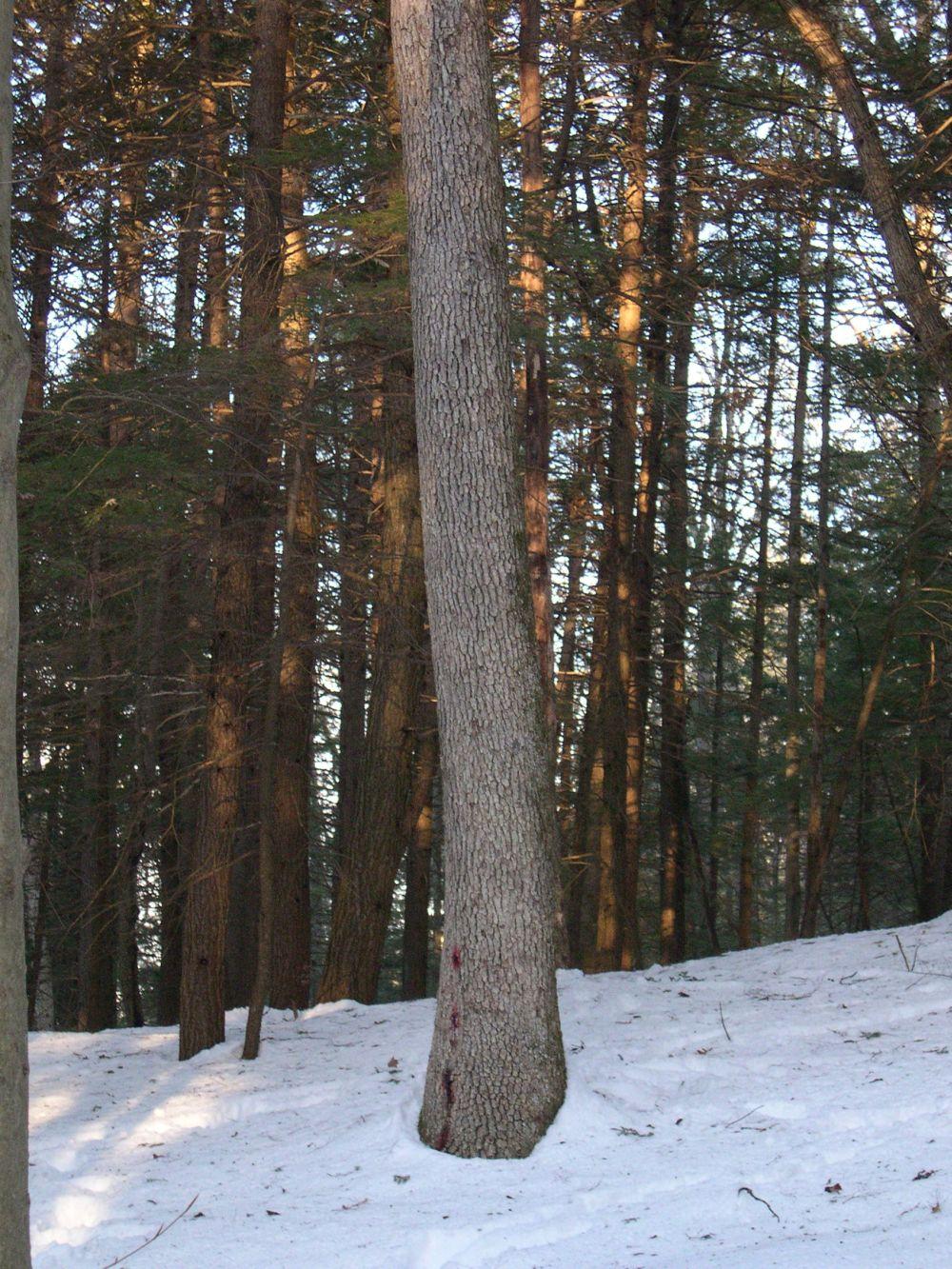

The tall, old white oak at the back boundary of the woodlot. Photo Dave Anderson

What we learn from our elders if we make time to visit.

Do you remember the celebrated New York City “Survivor Tree?”

New Yorkers found the stub of an ornamental Callery Pear buried beneath the rubble of the World Trade Center towers after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack. It survived. They moved it to a nursery, nursed it back to health and replanted it back at the September 11 Memorial site in 2011.

Many lesser-known and unsung “survivor trees” – trees bearing scars of time and tempests – hide in our forests. Gnarly old trees can connect us to a long history of fires, ice storms, hurricanes, tornadoes and floods. Imagine the broad sweep of historical events they’ve lived through! Trees now 150 years old, for instance, were mere seedlings in 1863 when President Abraham Lincoln faced a divided nation’s darkest days.

There’s one old white oak I like to visit. I guess you could say it’s become one of my favorite trees. It grows in a quiet and scenic spot on a south-facing slope overlooking a seasonal brook. Opposite faces of the old oak sport rusty stubs of imbedded barbed wire, dimples in its rough complexion of thick bark ridges. Facial scars from a surveyor’s blazes chopped by hatchet are marked by red paint. Fallen strands of barbed wire lie buried alongside, beneath six inches of soil created by decades of rotted leaves. The wire connects to a red maple up the hill, and finding it brought great joy because it confirmed the missing boundary of my woodlot, otherwise outlined by stone walls.

The oak is a reliable witness to the history of that particular place. It grew on the dry, well-drained slope surrounded by older American chestnuts. The oldest hand-drawn survey map for my neighbor’s woodlot to the east refers to his adjacent land as “The Chestnut Tract.” Today there is not even a stump left from chestnuts that succumbed to the fungal blight in the decades after 1905.

Further upslope, amid granite ledges of an old graphite mine, is a forest of Red Oak and Hop Hornbeam. The trunks of the oldest and largest red oaks exhibit uphill-facing basal fire scars that bear witness to fires either lightning-set or due to carelessness.

The worst recorded forest fire season in recent history in New Hampshire took place in October of 1947 after months of prolonged summer drought. Since oaks are better adapted to fast moving ground fires than some other species, it makes sense that my white oak and the red oaks would have survived those fires or others to remain today, while less fire-adapted species like beech, birch and maples would have succumbed.

A visitor looking over the Lane River Valley from this same hillside prior to 1900, would have seen rolling pastures entirely cleared of trees. The young white oak carried its three strands of barbed wire while overlooking a rough expanse of boulder-strewn land and grazing sheep or cattle before the turn of the 20th century. The decades-long wool craze briefly reigned the landscape between 1810 and 1840. Naturalist Tom Wessels had dubbed this era as “sheep fever” for a near cult-like devotion to raising sheep. Our forests continue to rebound to this day.

The farmers who cleared forests south of the White Mountains to pastures prior to the Civil War created a short-lived pseudo prairie. Tree cavity-dwelling wildlife specifically adapted as mature forest specialists – flying squirrels, fishers and pileated woodpeckers – decreased. Grassland specialists arrived and increased in abundance: meadowlarks, bobolinks, woodcock, red foxes and woodchucks.

When farmers moved on, pastures quickly reverted back to forest. Pioneer trees – sun-drenched white birch, poplars and white pines – replaced dark forests of beech, sugar maple, yellow birch and hemlock adapted to shade. The pastures of my woodlot were uniformly abandoned following the 1929 stock market crash and the ensuing Great Depression. When I cut a tree regardless of species or diameter and count growth rings, I find myself back in the early 1930s when I reach the core.

Now surrounded by dense hemlock and red oak woods, the white oak is declining in vigor and slowly dying of age-related effects which foresters and gerontologists call “senescence.” Yet even in decline, the oak bequeaths an important biological legacy. Large fallen limbs and dead wood are full of wood-boring beetles, millipedes, ants and grubs. Hollows provide nest sites for cavity nesting birds – woodpeckers or owls. Various entrances to hollow sections of trunk create long-lasting dens which may be renovated by mice, flying squirrels, raccoons, porcupines and fishers.

With current concern for which tree species and forest communities are best-adapted to compete in the changing climatic regime, survivor trees represent a century or more of natural selection and resilience. Changing suites of wildlife and natural communities shift and disappear while yielding to better-adapted or weedy species. In slow-motion it seems, forests respond to natural disturbances and landscape change. Even as individual trees succumb, forests endure.

The white oak “witness tree” is a living time-capsule that places my brief tenancy as landowner into its proper perspective. I hike down the hill after visiting the old oak with renewed perspective. If I squint my eyes just right, I might see myself descending through former landscapes my predecessors would instantly recognize…. And I wonder what changes the next 150 years will bring to our state’s forests.