Study aims to date stone structures at Monson Center

NH Division of Historical Resources archaeologists Mark Doperalski and Tanya Krakcik begin evacuation near the Nevins foundation. (Photo: Carrie Deegan)

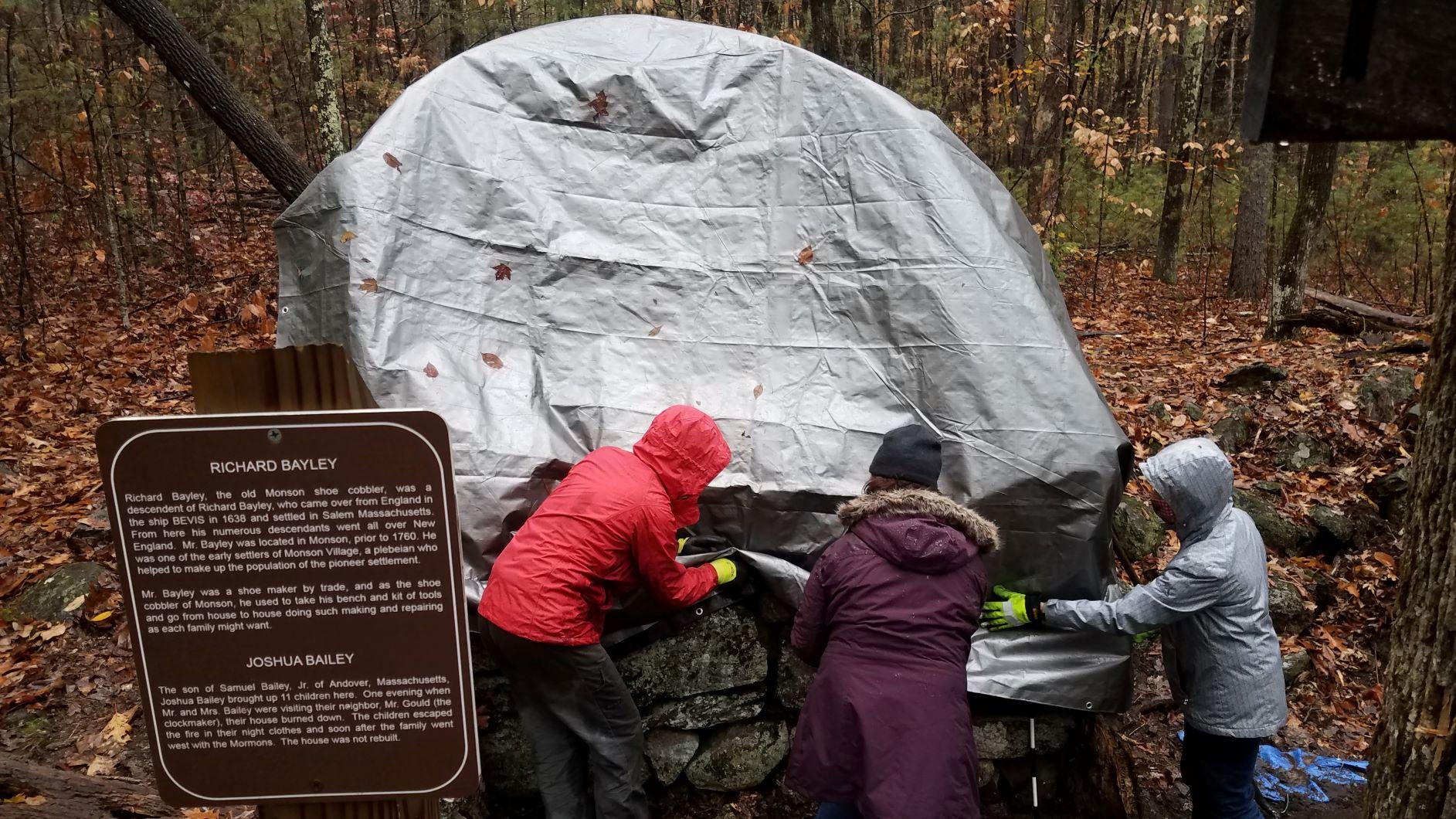

On a drizzly morning at the Forest Society’s Monson Village in Milford, N.H., a group of archaeologists and volunteers from the New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources (NHDHR) and New England Antiquities Research Association (NEARA) have erected a dome tent overlaid with several tarps above one of the property’s many historic cellar holes.

The scientists and researchers, led by New Hampshire State Archaeologist Mark Doperalski, aren’t searching for artifacts left by settlers during Monson’s short life as New Hampshire’s first inland colonial settlement. The tent and tarps aren’t even for protecting their investigations from the weather. Rather, the group is testing a method of archaeological dating called optically stimulated luminescence (OSL dating) which could help archaeologists and historians across New England determine the age of man-made stone structures.

Developed in the 1980s, OSL dating has typically been used in the Northeast to age layers of geologic sediment, not date the construction timeframe of stone structures. The method exploits the fact that minerals such as quartz and feldspar (the main components in granite), when buried, absorb and accumulate natural radiation that exists in the sediment. The longer they are buried, the more ionizing radiation accumulates within the crystals. When the rocks are exposed to light, the stored energy is released into the atmosphere in a matter of seconds.

OSL dating works when buried rocks or sediment samples are collected in complete darkness and brought to a laboratory where they are exposed to blue-green light. Upon exposure, the luminescence signal emitted by a sample is captured and measured using specialized equipment. The larger the signal, the greater the time that sample has been buried.

In the case of Monson Village, there is considerable confidence that all of the structures in this settlement were constructed between 1737 and 1770, when the village was mysteriously abandoned. Substantial historical research has been conducted on each of the former homesteads as well as their occupants. One of the two cellar holes that Mark Doperalski’s team is working on, for example, was constructed by Thomas Nevins Jr., who was born in 1711 on a ship in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean heading to the New World from Northern Ireland. He married in 1745 and had eight children born at Monson Village between 1746 and 1761.

“The fact that we know so much about Monson Village,” Doperalski explains, “makes the site a perfect place to test the accuracy of OSL dating for this application.” In essence, Monson is the control in this effort to determine whether OSL dating could be used locally to date structures of unknown origin and timeframe.

If you’ve spent any time in the woods in New England, you know that stone structures are commonly found in the forest. Cellar holes, stone walls, and old wells are abundant, but so are seemingly random rock piles or cairns.

“Some of these piles can be as large as a room,” says Donna Thompson, project coordinator for NEARA, the organization funding the OSL dating study. Other rock piles are much smaller, but regardless of size, many are of unknown origin. We understand from oral histories that indigenous people living in what is now New England may have built cairns to commemorate significant events or individuals. It is very difficult to tell, however, whether a discovered cairn is of indigenous origin or the result of a colonial settler clearing their fields for cultivation.

As a part of this OSL research project, rock and soil samples were also taken from two stone structures at Bear Brook State Park in Allenstown, N.H.

“There are stone piles at Bear Brook that are six feet high, and some are elaborately constructed with larger stone on the exterior and smaller stones inside,” Thompson says. It’s hard to imagine a colonial farmer bothering to engineer such a complex formation, but as she points out, that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.

After what seems like a long time, Doperalski emerges from the tent with two parcels about the size of cracker boxes, well wrapped in aluminum foil and then black plastic. It can be tricky to secure samples that have been undisturbed since construction, but Doperalski is confident these samples had not been disturbed since the Nevins home was built because of the way the stones were deliberately fitted together and still oriented horizontally.

The two samples will be sent to two different laboratories, one in Washington State and one in Colorado, for OSL analysis. The duplication is an additional effort to validate results and rule out processing errors. Scientific rigor meets Yankee conservatism at its best.

“The best case scenario is that both labs return similar results for each of the Monson and Bear Brook samples, and that the age of the Monson samples is within the known range of possibility for the settlement,” Donna Thompson explains. “That would indicate that OSL dating of stone structures may be a useful tool for our community.” Connecting archaeologists with more and better tools is definitely the end goal from NEARA’s perspective.

Unfortunately, the research team won’t know the full picture for more than a year. After the samples are analyzed, the laboratory results will need to be adjusted for the amount of local radiation in New Hampshire’s soils. This data will take a dosimeter about 11 months to collect at each site. It’s a long wait, but archaeologists are patient people, conditioned to thinking in centuries instead of decades or years.

“In the end,” Doperalski says, “it doesn’t matter whether these historical structures have been here for a couple hundred years or a couple thousand. Either way, it’s still important to preserve them.”

Carrie Deegan is Community Engagement & Volunteers Director for the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests. Contact her at cdeegan@forestsociety.org. This article was published in the Winter 2021 issue of Forest Notes magazine.