- Tags:

- Recreation,

- Wildlife,

- Education

Since mid-March, my family and I have been doing a lot of walking in the woods. Daily hikes on quiet, local trails have become our sanity in this constricted and complicated reality that we are living in.

Padding softly among the trees and moss, watching ducks glide through open water, or hopscotching slippery rocks to cross a rushing spring stream — these are the moments where everything feels most normal.

So, too, does picking off the ticks when we get home.

So far we’ve plucked at least a dozen ticks from pant legs, jackets, and our dog, and all of them have been black-legged ticks (aka deer ticks), the type that carry Lyme disease.

I wondered why, seemingly all of a sudden, we have an abundance of deer ticks when I have only ever found an occasional one in previous years. These musings led me to a conversation with Dr. Kaitlyn Morse, founder of the nonprofit BeBop Labs in Salisbury, where I found an answer to my question as well as some fascinating and surprising information about ticks and tick-borne disease in New Hampshire.

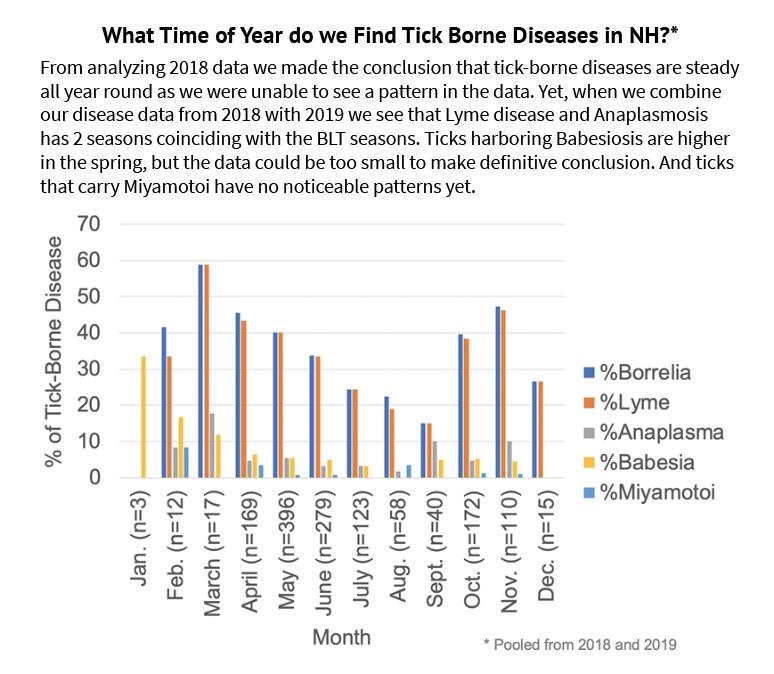

There are two “high seasons” for encountering black-legged ticks in New Hampshire, and just one for dog ticks.

For the past two years, BeBop Labs has been crowdsourcing the collection of all types of ticks from citizen scientist volunteers across New Hampshire. They have received thousands of ticks and have compiled a comprehensive database of when and where people are finding different tick species.

It turns out New Hampshire residents are picking up black-legged ticks early in the year, typically starting in March and peaking in May, followed by a lull in the summer and then a second spike in October. By contrast, dog tick encounters peak just once, in June, with most samples between April and August.

This explains my recent tick encounters being skewed exclusively towards black-legged ticks, and my surprise at finding so many of them is likely an artifact of our current situation: I’m hiking during mud season more than ever before.

Don’t worry much about dog ticks, but do worry about other tick-borne diseases in addition to Lyme disease.

Being able to identify the ticks you find can be helpful, as you are unlikely to pick up a tick-borne disease in New Hampshire from a dog tick.

BeBop Labs primarily tests black-legged ticks, but of the 1,300-plus dog ticks they have tested in the past two years, only two (0.15%) carried a disease. That’s extremely low, compared to the 41% overall for black-legged ticks in the last two years.

If you can confidently say it’s a dog tick you were bitten by, you don’t have to lose sleep wondering if you now have Lyme disease. If it was a black-legged tick, you unfortunately not only have to worry about Lyme, but also a growing list of other tick-borne diseases circulating in New Hampshire including anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and miyamotoi.

Never heard of some of these? You’re not alone.

Babesiosis is caused by a protozoan carried in the blood, and miyamotoi by bacteria similar to the one that causes Lyme disease. Horrifyingly, there are at least 27 kinds of bacteria in that same genus, Borrelia, that each cause different tick-borne diseases. Some are carried by ticks that don’t bite humans, but others, like Borrelia miyamotoi, do make people sick.

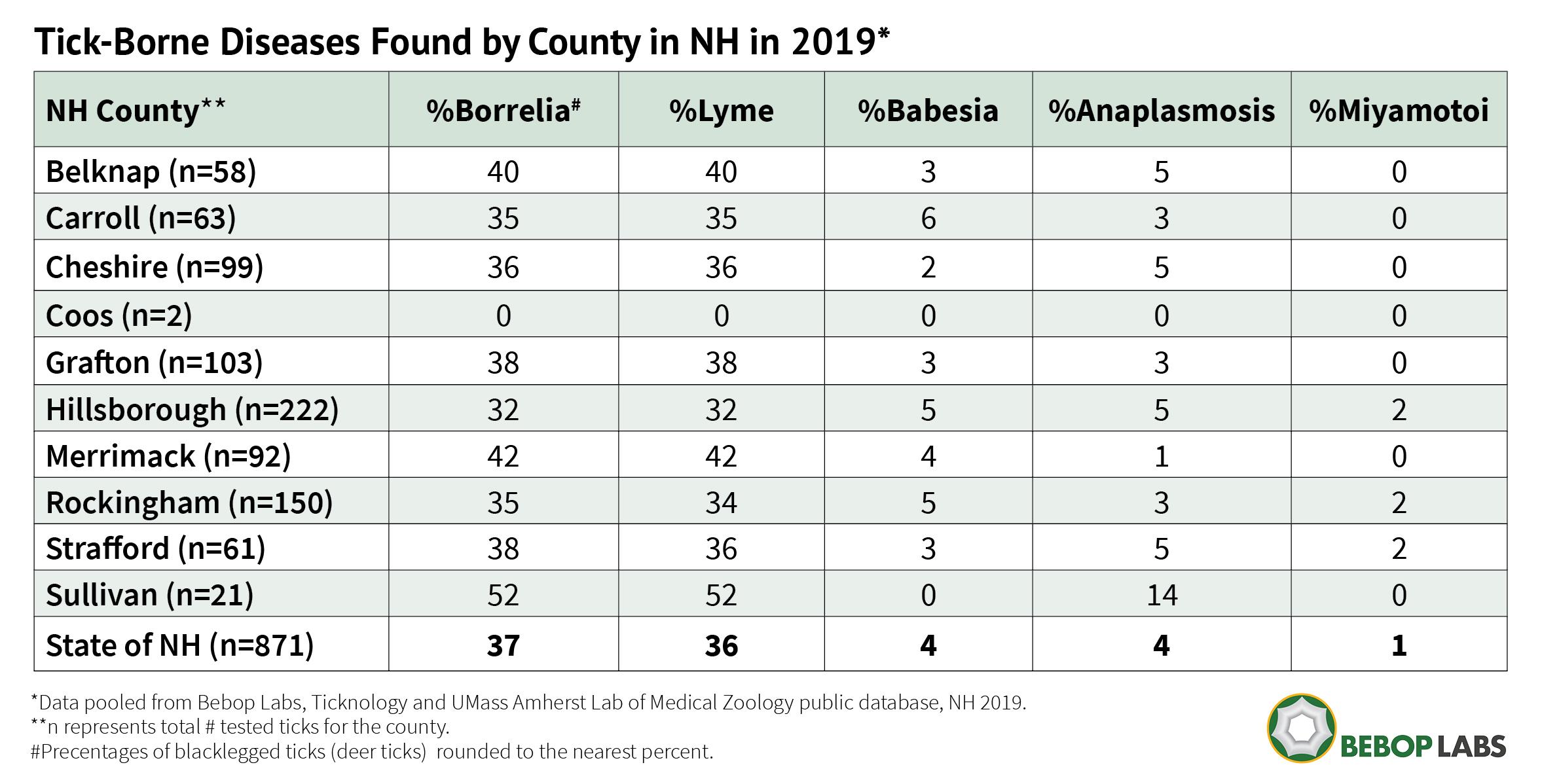

Lyme is still the most common disease carried by NH’s black-legged ticks (about 40% statewide in the last two years), but a significant percentage of them also carry babesiosis (about 5%), anaplasmosis (about 6%), and miyamotoi (about 1.5% and rising).

Certain people really are “tick magnets.”

If you’ve noticed that your husband or your hiking buddy tends to pick up a lot more ticks than you do when you’re walking the same trails, you’re not just imagining it. There are specific traits that make certain people more attractive to ticks — as Dr. Morse says, “hot, hairy, heavy breathers tend to be tick magnets.”

Ticks are attracted to heat and carbon dioxide, so people with higher body temperatures and those exhaling forcefully are at greater risk. Hairy legs and arms are also perfect “legholds” for ticks to grab onto as you brush past them in the woods or a field edge. And if you don’t fit this description but still tend to pick up a lot of ticks, there’s also an X factor- some people release greater amounts of a chemical pheromone called butyric acid in their body odor that also acts as tick bait.

If you know you are a tick magnet, take extra precautions to tuck pant legs into socks, consider treating clothing with permethrin, and check yourself thoroughly following outdoor adventures.

Overall, New Hampshire is a hot zone for tick-borne disease. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) tracks the incidence of diagnosed tick-borne diseases in each state and NH consistently rates in the top five states in terms of cases per 100,000 people.

That’s a dubious honor, to be sure, but the chances of contracting a tick-borne disease are not uniform across the state. This is where BeBop Labs is providing information that is unavailable elsewhere and critical to understanding your risk, whether you’re in Manchester, the Seacoast, the Monadnock region or the Great North Woods.

For example, if you were bitten by a black-legged tick in Cheshire County in 2019, where 35% of the black-legged ticks were infected with Lyme disease, you were less likely to contract Lyme than if your tick came from Merrimack County, where 42% of BLTs were infected.

Complicating matters, infection rates also change seasonally, as ticks move to host animals that may have higher rates of infection with a pathogen.

Dr. Morse notes that, “It is BeBop Lab’s ultimate goal to develop methods of getting our scientific information directly to people where they recreate, via signage at parks and trailheads, or a mobile app that people can use anywhere to accurately assess their risk of infection based on location and season.”

In the meantime, you can easily review their data online to understand what types of ticks you’re likely to encounter in any region of the state and the probability that they are infected with each tick-borne disease.

If you want to know if you have contracted a disease from a tick bite, you might be better off testing the tick.

The typical method for finding out if you may have contracted a tick-borne disease involves waiting a month after the tick bite and testing your blood for antibodies specific to these diseases. The problem with this approach is that different people develop antibodies at different rates and in different quantities, which means the results from this test are notoriously inaccurate (anywhere from 18% to 72% accuracy, depending on the study).

In contrast, if you save and test the tick itself for disease (which you can do), this test has 99.9% accuracy in revealing the specific diseases the tick is infected with.

Getting a positive tick result doesn’t necessarily mean that disease has been transmitted to your body, and Dr. Morse is quick to point out that people should always seek the advice of a medical professional when considering important health decisions.

That said, testing a tick can take less than a week, giving you results in plenty of time to start an effective course of treatment if recommended by your physician. There are several labs that test ticks and provide results to the public, including one at UMass Amherst (tickreport.com, $50) and another called Ticknology (ticknology.org, $25) based in Colorado.

BeBop Labs tests ticks for free, but only as funding allows and with no guaranteed turnaround time, so if you are worried about a particular tick bite it may be wiser to go with a paid option.

You can help increase our knowledge of tick-borne diseases in New Hampshire.

If you find a tick anywhere in the state — of any type or size — you can help contribute to the knowledge base of tick-borne disease distribution in the state by sending it in to BeBop Labs. The Forest Society’s volunteer land stewards, who are out monitoring conservation properties, sent in 65 ticks last year. I’ve already sent in three this spring. There are detailed directions for how to do this and what information to send with your tick on their website (www.beboplabs.org).

BeBop Labs is an all-volunteer non-profit organization, so although they will happily take and test your tick at no cost to you aside from the stamp to send it in, they also welcome donations.

Their crowdsourcing approach has resulted in some of the most robust data on tick-borne diseases in the nation, and their tick mapping program has become a model for similar initiatives in other states and in countries as far away as the Netherlands.

As you get outside for local hikes this spring, stay vigilant for ticks (they aren’t interested in social distancing), arm yourself with the best available knowledge, and consider engaging as a citizen scientist too!