- Tags:

- Working Forests,

- Stewardship

AS I WRITE these words in late April, the wind is gusting and swirling outside. (And in truth, in my old house, there's a noticeable breeze inside as well.)

I watch as the catalpa tree by the barn twists and bends, not so much in defiance of the wind as in compliance with it. That particular catalpa, I know, was planted as an ornamental by a previous owner of the property in the 1950s, meaning that it has survived the gusts for 60 years. Perhaps it has been helped by the fact that catalpas' large leaves come late, long after these spring winds.

Behind the barn, an ash tree - certainly bigger and likely older - stands sentry over the horse paddocks. It might have started duty guarding cows (for which the barn was clearly built) or sheep. Its branches reach out from low on the trunk and collectively create an impressive crown that, once leafed out, provides the kind of shade on a hot July day that brings it companionship in the form of a tuckered-out dog or a lazy landowner whose sole aspiration for the afternoon is the consumption of a cold beverage.

This is a tree that has grown unsurrounded by other trees, in full sunlight, perhaps itself shielded from blustery prevailing winds by the barn.

Watching these two survivors bend in the wind makes me wonder to what extent tree fiber has adaptive qualities, like human muscle. Do trees like the catalpa and the ash survive in part because they remain "fit" and "flexible?" When I ask such questions of foresters, I often get a look that suggests they'd like to fire up a chain saw on the spot and drop me to the forest floor, a look followed by a heavy sigh.

However they manage to grow, big trees serve as a source of fascination. Part of this is from a presumption that the biggest trees are the oldest, which is not necessarily the case. Slow-growing species like Black Gum, for example, can be hundreds of years old without becoming massive. Trees grow large over time, to be sure, but more likely they've enjoyed ideal conditions -the right soil, sunlight and moisture - to keep growing.

And often a big tree has just gotten lucky enough not to get in the way, become of a form that diminished its commercial value and then been rewarded with a caretaker who tended to its aging limbs.

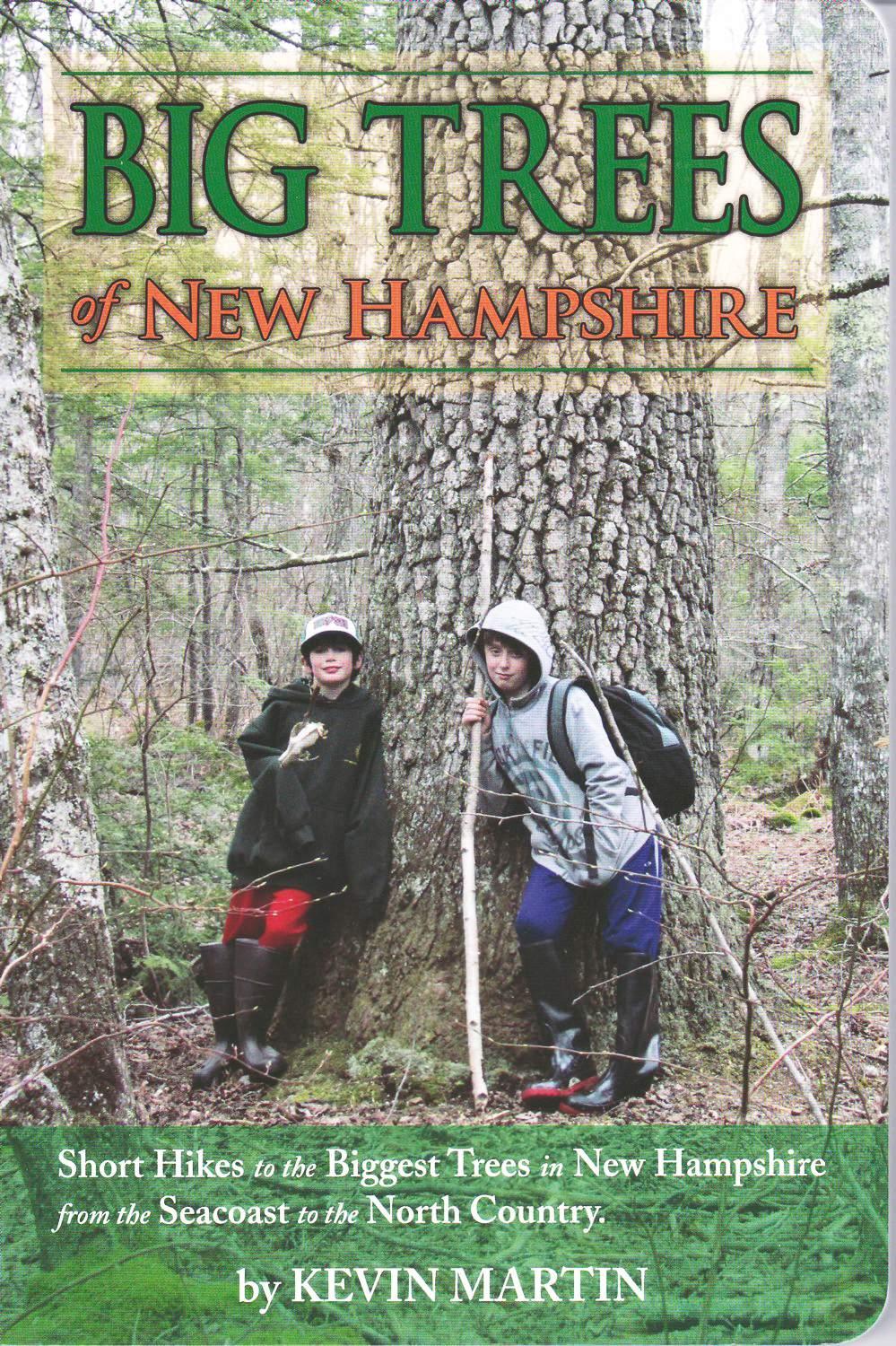

Such caretakers include Kevin Martin, the author of a new book called "Big Trees of New Hampshire: 28 Short Hikes to the Biggest Trees in New Hampshire from the Seacoast to the North Country." Martin is the Rockingham County coordinator of the state's Big Tree Program, though he's probably better known as a builder of wooden boats and canoes (http://kevinmartin.wcha.org), which has led him to a lifelong appreciation of wood and the trees that provide it. Martin lives along the Lamprey River in Epping.

The New Hampshire Big Tree Program started in 1950. Volunteers in each county identify and document the biggest examples of individual trees of a given species. To date, they have found more than 700 big tree champions, including seven national champions. You can find out more about the Big Tree Program - including how to measure a potential champion or become a volunteer - at http://extension.unh.edu/Trees/NH-Big-Tree-Program.

But if you'd just like to go see a big tree or two - or 85 - "Big Trees of New Hampshire" can be your guide. Martin has identified 28 hikes that will take you to some of the largest trees on public land and offers insight into their history, management and caretaking. Some of these big trees are in the city, (such as the horse chestnut planted in Portsmouth by a signer of the Declaration of Independence), meaning that they don't require epic hikes to find them.

If you'd like to get a copy of Martin's book, check with your local bookstore, visit www.enfielddistribution.net/bigtreesofnewhampshire.aspx, or call Enfield Distribution at 632-7377.