"Franken-forest" tough, resilient and under pressure

- Tags:

- Creek Farm

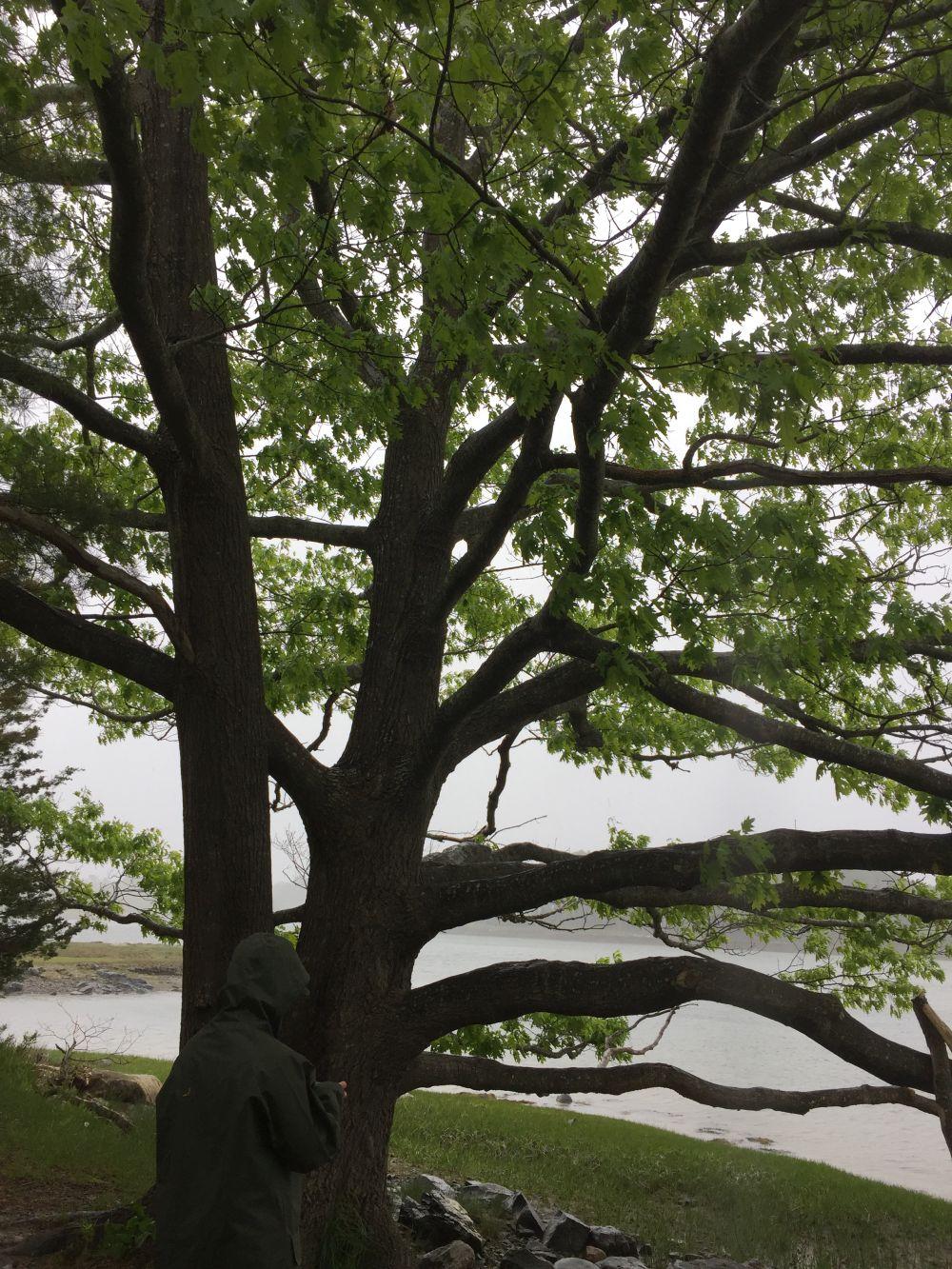

Red oak and white pine forest on the terrace above Sagamore Creek at the Creek Farm Reservation. Photo: Jack Savage.

Where once-vast inland forests meet the rocky extremes of coastal rivers and shallow brackish, tidal estuaries, the combined effects of weather, past agriculture, development pressure and recently introduced landscape trees and aggressive invasive plants contribute to a kind of chaotic “Frankenstein forest.”

Located on Sagamore Creek in Portsmouth, just inland from the open ocean beyond Rye and New Castle, Creek Farm Reservation is owned by The Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests. Its 35 acres includes oak and pine forest, former agricultural fields and fresh and brackish wetlands that provide habitat for resident and migrant birds and mammals.

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing management planning of NH's easternmost forests is defining what forest conditions are most natural. Weather, soil and a long history of intensive human land use have given our coastal forests a scrubby appearance and a resilient character.

“Succession,” is the term foresters use to describe how open fields revert to mature forest after mowing or grazing ends. The process is a slow motion relay race as sun-loving plants are gradually replaced by shade-tolerant trees. Sun-loving “pioneer” trees include white pine, red cedar, balsam fir, white birch, cherry, aspen (aka poplar) and gray birch. Once partial shade is established, red oak, white ash, red maple and yellow birch replace the pioneers. Last to arrive are shade-tolerant spruce, sugar maple, beech and hemlock.

Native red oak and white pine are particularly well-adapted to the coast. Their seedlings must compete for space and sunlight with non-native shrubs and ornamental trees escaped from suburban streets and gardens. Invasive shrubs at Creek Farm include autumn olive, common buckthorn, Japanese barberry, European barberry and honeysuckle. Entwining vines include thorny green briar and climbing bittersweet with its colorful yellow and red fruits. New arrivals include more aggressive plants which outcompete native vegetation and exclude native plants from the relay race of succession.

Creek Farm also includes cultivated trees that have escaped from nearby designed landscapes. Apple, pear, red cedar, mountain ash, honey locust, horse chestnut, butternut, black walnut and Norway maple trees have seeded-in and now grow wild among native white pine and red oak woodlands found along Sagamore Creek. The 1.5 mile Little Harbor Loop Trail passes through forests containing both native and non-native introduced ornamental species at Creek Farm.

Another stress on coastal forests is extreme weather. Salt spray and high winds from severe storms including summer or fall hurricanes and winter Nor’easters are unique to the coast. Imagine concentric rings spreading northwest, inland to the White Mountains. Each ring defines a statistical decrease in the average return interval for major hurricanes in New England. Pitch pine woodlands with a tenacious understory of poison ivy, sweet fern, bayberry, wild roses thrive on the shifting sands of natural back dunes at Cape Cod. The most heavily disturbed sites lie closest to the open ocean. While wind and salt cause damage, open water along tidal creeks and estuaries helps to moderate extreme cold winter temperatures found inland.

Undeveloped woodlands near the water’s edge are increasingly rare as human development continues to claim the more valuable land: first for working farmland and now for waterfront luxury homes. Sandy soils of the NH Seacoast region that grow red oak and white pine forests had long-experienced disproportionate development threats: the landscape is relatively flat and well drained. As residential development replaced rolling farm fields, even red maple forested wetlands, salt marshes of Great Bay, and rocky ridges separating tidal creeks were no longer worthless or unproductive. The scenic views of open space add a premium to soaring Seacoast real estate prices.

Remaining fragments of waterfront woodlands allow us to imagine how the Seacoast region may have appeared centuries ago. Even as coastal forests recover from frequent storms and from former agricultural uses, these same places face new pressures from encroaching human development and from increasing competition from non-native plants.