- Tags:

- For Landowners,

- Something Wild

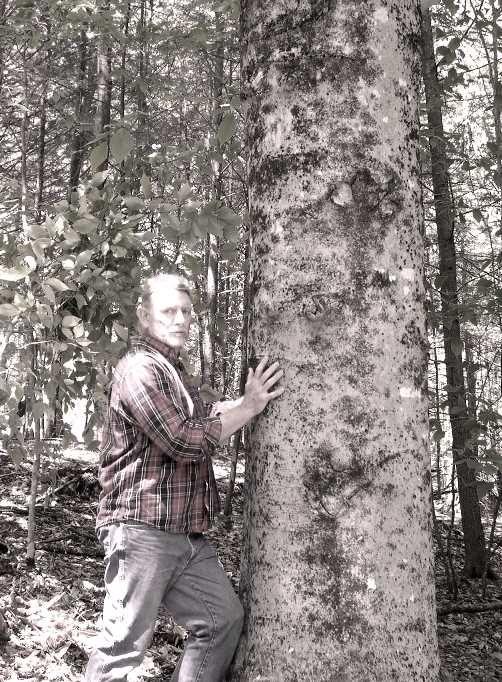

One very old beech tree, in the corner of the woodlot, resembles a totem pole. (Photo: Dave Anderson)

“Senescent” comes from “senile” – the aging process. The word is disconcerting as we prepare for the summer wedding of my eldest daughter. She wants to start her family… becoming a grandfather is now inevitable. It’s shocking.

I seek solace in the forest. I veer off the woods road to visit some of the oldest trees of the woodlot. There’s a red oak now too old to cut for lumber. Its gnarled bark is full of craggy cracks and checks. Broken limbs and hollow cavities reveal interior rot. A wealth of boring insects attracts woodpeckers who glean the standing ancient for breakfast. That oak once shaded livestock in what was an open pasture.

Birches die at 100 years; oaks and pines might live to 150 years or more. The craggy sugar maples along the stonewall live 250 years. Hemlocks and beech live longer still.

The young woods surrounding me are adorned in tender leaves. Branches and twigs resound with the dawn chorus of songbirds preoccupied with hidden nests of eggs. As youthful exuberance goes, it’s hard to beat this first week of June.

One very old beech tree, in the corner of the woodlot, resembles a totem pole. It’s elephant-gray bark is etched with uncanny facial features: deep-set eyes, crinkles and fine lines of crows’ feet. I rest my palm against its ancient mossy trunk…“How can I be a grandfather?” I ask him.

The tree projects a wry smile and I hear its inaudible answer, “in due time.”

Old trees connect us to earlier times. As survivors, elders and ancients provide metaphors hard to ignore. To visit them is to evoke the sense of long, slow time which ultimately sweeps our own lives along. One could do worse than admire old trees.