- Tags:

- Wildlife,

- Something Wild

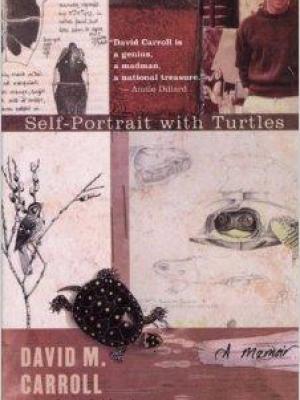

David Carroll with field notebook.

Something Wild takes pride in introducing residents of the state to the wonder in the wild that surrounds us all. Someone who discovered that wonder at a young age is David Carroll. “I was 8 years old when I had that experience with the first spotted turtle,” said Carroll, a naturalist, writer and artist who lives in Warner.

But that first experience of his set him on a path that returned him frequently to the swamps around the Connecticut home of his youth. “I just went there to be there to be alive there to get lost in that world to enter into that realm.”

His swamp walks led him around that realm…and took him on a course of discovery and wonder not uncommon to naturalists. “You just see something in nature and you say, ‘I can’t believe that.’ As you come to have a relationship with it, even if you don’t understand it in a profound scientific way it just tells you there is more that is beyond human life or different from that.”

His endless meanderings made him a witness to the ever changing landscape around him. “I saw this landscape of loss as it was happening. I still remember those places I walked. They don’t exist anymore but I remember them. That has always haunted me.” Carroll may be sentimental about habitat loss, but he’s also a realist and he knew that simply pining for those ecosystems wouldn’t help to preserve them. So he began advocating preservation when he moved to New Hampshire around 1970s. “I fell in love with the landscape as much as with the turtles. They are inseparable. When the landscape goes, everything goes with it.”

"I can’t get on the 'Last Child in the Woods' bandwagon."

Carroll coached land trust groups about preservation, lobbied officials and spoke to school children, earning him another descriptor – “The Turtle Guy” – but over the years his message changed. “I don’t see the natural world as the cure for human dissatisfactions or disappointments, it is a much more sacred thing than that.” He disagrees with Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods, in which Louv laments what he coined as "nature-deficit disorder", and argues that all children need to experience nature. “I gave a lot of talks in schools. I’d show them slides of the places I go, and I talk about vernal pools. And I say, “I would love to have you see a place like this, but there are 55 of you. That’s 110 booted feet. The landscape can’t bear that. It’s just impossible.”

Carroll objects to conservation efforts that too frequently hinge on the use humans can make of a given piece of land. He thinks we miss the point when we speak of nature in terms of how it can serve us. “Let’s have some places like that, but where do we truly give equal rights to nature?”

That’s where preservation comes in. Carroll argues that we need to preserve tracts of land beyond the reach of human accessibility to protect the ecosystem, of which we are a part.