Nature's View

- Tags:

- Forest Society History

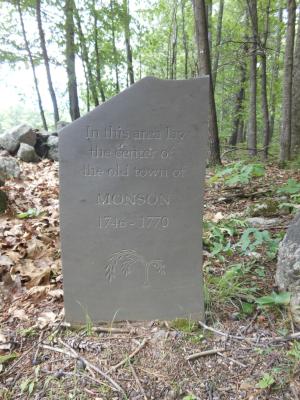

Among the unsung attributes provided by permanently-protected, conservation land is the quiet, spiritual sense of slow time – an endangered experience in our contemporary landscape. Monson Center Reservation, Milford & Hollis. Photo Carrie Deegan.

Morning chores offer a brief, yet vital connection to the land, a respite from the rapid pace of instant communication and the perils of electronic overload: a continuous stream of news, weather, sports and entertainment. The pace of modern life and its constant rapid change are like fresh concrete and asphalt: abrupt, jarring and irreversible. In comparison, the slower pace of natural change – weather, seasons and forest succession – are reassuring and timeless.

Seasonal outdoor work – mowing fields, weeding gardens, raking leaves, splitting wood, hauling water and shoveling manure become a kind of ritual labor, rich in repetition like chanting of a mantra. The daily farm chores reconnect me to outer weather, moon phases, wildlife and birds as harbingers of each season. While fetching water, spreading hay and driving sheep from pen to pasture, I witness the subtle changes in the angle and quality of sunlight or maybe glimpse a deer bounding over a stone wall.

The connection back to the land is a tie that binds me to my predecessors. I sense their fleeting shadows and hear a sound like muffled speech in the rustling leaves. Morning dew in pasture grass reveals faded footprints along a faint path to the well, topped with its red, cast iron hand pump. That creaking pump arm is cool to the touch even in mid-summer. Bright water rises quench its gulping throat and then spills like liquid birdsongs in the apple orchard. The pasture is lush green, studded with dandelions and hovering bees.

Plaintive bleating from a wobbly, frightened lamb summons a low-pitched "baaa" of reassurance from its mother. In an instant, time stands still… bleating sheep and creaking well pump conjure the legacy of lost farms, a ghost song that recalls the vast open pasture landscape of old New Hampshire, a landscape forgotten for a century or more.

Old cellars flanked by tumbled granite walls and hidden wells and twisted apple trees were once common in the forest of southern New Hampshire. A thick and palpable sense of history lies heavy in these remaining woods. A veritable flood of trees inundated the hills and valleys once entirely cleared as farms well before the mid-nineteenth century. Decades now accumulate like layers of fallen leaves obscuring the past.

The Forest Society's land reservations harbor many important, undiscovered cultural artifacts. Old roads, dooryards, cellars, wells, privy sites and long-buried trinkets, including bottles, steel wagon tires, bits of tin, rotted leather and fragments of painted ceramic all remain undisturbed, preserved in place.

One such tract – Monson Center, in Milford and Hollis – was ultimately saved by its own history. One of the state's earliest inland settlements settled in 1737 by the Nevins family, the former town of Monson Center was threatened with destruction in 1997 by plans to build 28 new luxury homes. Today, The Forest Society's 220-acre Monson Center reservation offers a glimpse of colonial New England life in "Dunstable," then part of the northern frontier of the British-controlled Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Today, Monson Center is an outdoor museum where names of early settlers – Nevins, Gould, Bayley, Wallingford, Brown and Hubbard – are posted adjacent to the cellar holes of former homes. Those rugged settlers wielded their axes, crosscut saws, plows, hay rakes and pitchforks. They drove horses and used oxen to pull stone boats to build granite pasture walls. They worked themselves to death.

At dusk, shadows creep from crumbling cellars and fallen barn timbers, reflections appear in the crystal depths of granite-lined wells. Faint voices are overheard in the relict orchards and old burial grounds. Reading aloud the various names chiseled into old headstones will make the hair stand on the back of your neck. The "clip-clop" cadence of horse hooves echoes off marble and slate. It is as if the land itself remembers those names of early inhabitants. Few come to read old stones and stroll quietly amid the ruins of early New Hampshire. Authentic antique landscapes inspire a modern connection to what nature writer John Hay once termed our "sense of a great continent with a magical, ceremonious past."

While our ancestors drastically altered the landscape, clearing hill farms and building stone walls, ultimately the place we've inherited has recovered its original, wooded contours. But modern blasting, excavating, building, paving and real estate speculation are rapidly and permanently altering a quiet sense of history while foreclosing remaining opportunities to experience it. Among the unsung attributes provided by permanently-protected, conservation land is the quiet, spiritual sense of slow time – an endangered experience in our contemporary landscape.

When the roar of jets, highway traffic and construction drown out the quiet voice of history, then who will strain to hear the sound of trickling water? When the surreal orange glow of shopping plaza parking lot lights erase constellations from the night sky, who will recognize the myths of our own ancestors? The last echoes of our own history will fall silent and shadows in the forest will disappear.

Remaining rural landscapes engender the sense of following close on the heels of our ancestry. A reverence for history is best learned by listening and watching for clues to those who came before us – a legacy we may yet leave to those who follow us.