- Tags:

- Climate,

- Land Conservation

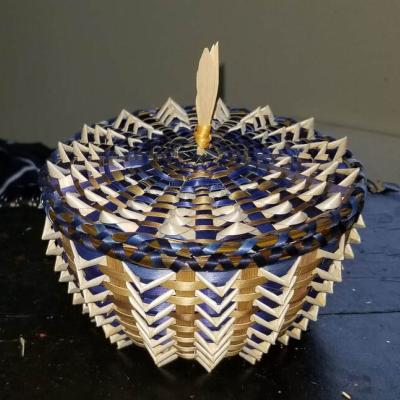

A basket made by Amanda Ennis on display at The Rocks' visitor center in the Carriage Barn.

What do forests mean to you? When the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests transformed a historic carriage barn into a modern visitor center on its conservation land at The Rocks in Bethlehem, the nonprofit organization asked visitors to share their answers.

One young person wrote: “It makes maple syrup and gives the mountains.”

Another visitor shared that forests “bring peace and calm.”

Others added “tranquility and beauty,” “fresh air,” and “home to animals.”

In an interpretive exhibit, the Forest Society highlighted and explained many of the benefits that visitors mentioned. Forests provide clean air and water, sustain our livelihoods, provide places to explore and play, and cool the climate.

Forests are also a tie that binds. And for Amanda Ennis, ash trees help carry on traditions like basket weaving.

Ennis, a Maliseet basket maker in Maine, created a gold and blue basket that is on display at The Rocks, illustrating another benefit of forests. For generations, indigenous people in the Northeast have carried on place-based traditions including weaving baskets using sweetgrass and ash trees.

Her baskets are also on sale in The Rocks' giftshop. (Learn more about her work on her website)

In a recent interview with the Forest Society, she shared more about her path to becoming a basket weaver and why brown ash trees are so important to her work:

Q: How did you get into basket weaving?

“I apprenticed with Sarah Sockbeson [a Penobscot ash and sweetgrass basket weaver] in 2013 or 2012. I was in college. I was in my third year of liberal arts over at the University of Maine in Augusta. … I thought this would just be a great project to do… to learn more about her art.

My tribe originated from Tobique [First Nation]. They have another one [tribe] in Houlton [Maine]. So, I just was very interested in it. … Through the Maine Arts Commission Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program, we were accepted.

I’m really lucky that I got that and that Sarah is so talented… I’m very lucky to have had her as a mentor.”

Q: How do you source the materials for your baskets?

“First we go on to the shores of Maine – I haven’t gone to do that yet.

[Sarah] actually goes on to the shores of Maine and she hand-picks every blade of sweetgrass… you can’t just grab a handful… it has to be picked in a very particular, certain way… to make sure that it’s very sturdy and that you can weave with it.

That takes almost a day or two to get a bunch of that sweetgrass that you need.

Then, we usually go into the forest. I’ve actually helped [Sarah]. I haven’t cut a tree down or anything … usually the Native American men will cut down a tree and split it. I tried to split a log once… (it) was too difficult.

Then, you pound the bark off and split the wood and then you have to take those pieces that split off the log and you have to put it in a special tool so you can make the pieces smaller and more pliable so you can weave the basket.

That’s what holds the basket together — the brown ash is a very important part.

How long does it take you, on average, to complete a basket?

It used to take me three or four days but now… I just completed a three-inch pinecone basket... that one took me about four or five hours for two days… Weaving is a very intricate... I usually only work four or five hours at a time.

It’s very rewarding when you get the basket done and looking at something you’ve created.

And everything I’ve created has come from a piece of wood — just a tree. It’s a very satisfying job.

How important is the brown ash tree to your work?

I don’t think there’s any other type of tree, honestly, that would produce the type of basket that I make. The wood in the basket and in the brown ash tree… it’s just so pliable. I’m not 100 percent sure on this because, like I said, I’ve only technically been weaving for four years now but, as far as I know, the type of wood that we’re using is sacred and there’s no other wood like it.

Is there anything else you’d like people to know or think about when they see your basket?

Let them how I make it, how it’s sacred art…

I don’t know if you’ve heard of the Emerald Ash Borer… it’s a type of borer that we’re trying to keep away from the brown ash tree so that we can keep the basket weaving going.

As Forest Society staff have written in previous issues of Forest Notes, the emerald ash borer (EAB) is an invasive forest pest that has been decimating native ash tree populations across North America since it was first detected in Michigan in 2002. The first sighting in New Hampshire was in 2013, and since that time this invasive insect has spread rapidly to nine of the state’s 10 counties. At the moment, there is little chance that we can prevent the near-complete loss of all of our mature ash trees.

See land conservation project manager Stacie Hernandez’s story on The Future of Ash Trees in New England in a 2022 issue of Forest Notes magazine.

(Note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.)