- Tags:

- Land Conservation

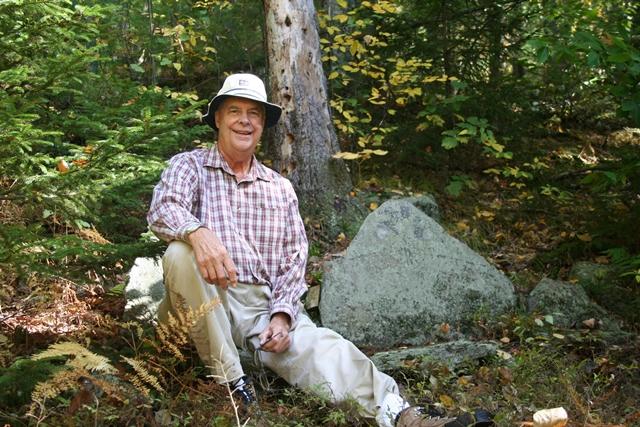

By donating a conservation easement on 55 acres of land off Route 124 in Jaffrey, siblings Ann Hamlen Goldsmith, Richard Hamlen, Katharine Hamlen Reed and Charles Hamlen have preserved the scenic hiking experience up Mount Monadnock’s Old Toll Road as well as along the Metacomet to Monadnock summit trail. Forest Society photo.

A walk in the woods is not just a walk in the woods for Richard Hamlen. When the woods are those his grandfather bought in 1906 at the base of Mount Monadnock in Jaffrey, the walk is more like a reunion with old friends.

That truck-sized boulder? It’s big-sister Ann’s Rock, and you had to be good to climb it as a kid to bug your sister perched up there all high and mighty.

And that’s not just a patch of trees beyond the house. No, that’s hard-fought ground won in water-pistol battles between siblings and friends. He can hear the hollering, still.

“In the 1950s, there was a very good squirt gun you could get at the Woolworth’s five and dime that had a very focused stream of water. We used to have some very fine water pistol fights on this mountain,” Hamlen, 77, recalled.

When the rocks and trees and slopes hold the story of a family’s good times for five generations, it becomes unthinkable that any of “this land that we know,” as Hamlen calls it, would be destroyed by development anytime in the future. So, donating a conservation easement on 55 acres of their land to the Forest Society became the ideal solution for Hamlen and his sisters, Ann Hamlen Goldsmith and Katharine Hamlen Reed, and his brother, Charles Hamlen.

“All this land that we’ve had such rich experiences with is going to be protected. The coming generations are going to have all that,” Richard Hamlen said.

The four siblings, who live in Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York, share the place that has been a summer retreat for generations of Hamlens. Their Scotland-born grandfather, Capt. Ewing Wallace Hamlen, and his wife Mary started the tradition by bringing their family to a seasonal home there from Cambridge, Mass., each summer. Friends came too, and Mary’s two sisters. They’d come by train as far as Troy, then take a wagon the rest of the way, with the men walking alongside the horses up the steeper hills.

It was during this time, around 1913, that Ewing Hamlen helped the Forest Society to conserve land around the summit of Mount Monadnock, an effort Richard and his wife Bard learned about through what Bard calls ‘serendipity.’

They bought a 2007 book called Monadnock, More than a Mountain by Craig Brandon, and were thrilled to find the Hamlen name in the index. It referred them to Chapter 13: “How Monadnock was Saved.” There, they read about the Forest Society’s efforts to stop overly enterprising businesses from claiming title to Monadnock land. Many tracts had unclear ownership, with deeds that dated back to Colonial grants from the British Crown. Ewing was an attorney for Abbott Thayer, the landscape artist who called on the Forest Society’s first president/forester, Philip Ayres, to protect his beloved mountain. Ewing helped Ayres track down the 77 long-lost descendants of the original grantees so they could be asked to sign their claim over to the Forest Society. They did, and 406 acres became the first Monadnock tract protected by the Forest Society.

For his grandchildren nearly a century later, learning about Ewing’s efforts made gifting the Forest Society a conservation easement on their land seem like a fitting tribute to him.

“In terms of protecting and conserving the mountain, what we’ve done is in the spirit of what he was doing then,” Richard Hamlen said.

The four Hamlen siblings spent their summers on Monadnock with their parents, Richard Sr. and Caroline Hamlen, and grandparents. It was a place of constant activity – climbing Monadnock more times than they can count, fierce tennis competitions on a clay court, picnics at Fassett Brook, singing joyfully along as their grandfather played Scottish tunes on his handmade violin while sister Ann played the grand piano. When they had children of their own, Monadnock again was the destination for summer vacations (Richard and Bard brought their second child Polly to the summit at 10-weeks old).

Chores, too, connected young and old to the land as much as the playing. Gathering wood, gardening, picking berries, clearing brush. And always, a connection to the land was a connection to the family heritage.

That’s why Richard Hamlen’s walk in the woods now isn’t complete without finding two things, and on a search this past fall he found them both. One is a stone seat made by Granddaddy Ewing out of flat slabs of granite. It faces west, and when his grandfather sat there to watch the sunset behind the hills, Richard said, “it reminded him of Scotland.”

The second is a towering mass of granite ledges, a destination for one of the stone paths his grandfather laid so many years ago. It rises up surrounded by trees and sky, the twitter of birds and nothing more.

“You can walk across the top,” he said. “You can imagine coming up here, to clamber all over and give heartache to your parents that you’re going to fall and break your neck,” he said.

He thought about climbing it for a moment, but the rocks were still slick from rain the night before. He thought better of it and just took a long look around.

“It’s going to be wild like this and not developed,” he said. “We’re very glad it’s going to be protected.”

Originally published in Forest Notes, Winter 2013