White Mountain National Forest Turns 100

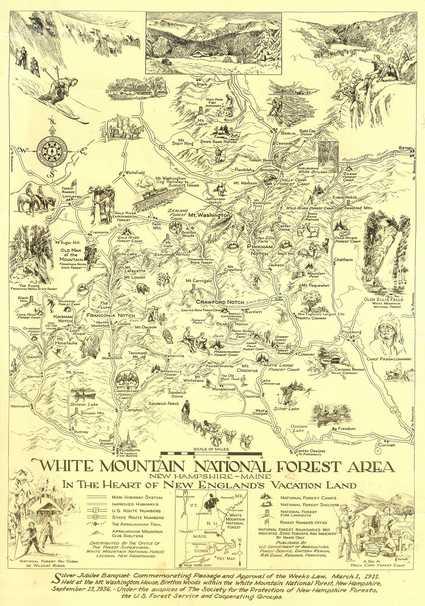

This map illustrated by Tom Culverwell was issued in 1936, 25 years after the passage of the Weeks Act, 18 years after the formal establishment of the White Mountain National Forest, and seven years after Philip Ayres 1929 report on progress.

We tend to take the White Mountain National Forest for granted. Seems like it’s always been there, and it’s hard to imagine that it wouldn’t survive us and many more generations to come.

But it was just 100 years ago this spring that the WMNF was officially established, when then-President Woodrow Wilson signed it into existence. That’s not a long time in the life of a forest. On May 16, 2018, the Museum of the White Mountains in Plymouth helped celebrate the birthday with the opening of its exhibit “The People’s Forest” running through September 12, 2018.

At the time, the official establishment of the WMNF seemed long overdue to those who had long fought for the creation of eastern National Forests. Forestland east of the Mississippi River was getting cut far too aggressively and without thought to long-term management. Fires burned slash on denuded mountainsides, in turn causing problems with runoff in streams high in the watershed, and thus rivers downstream.

The Appalachian Mountain Club, among others, had been advocating the protection of the White Mountains in particular for decades. The Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests was founded in 1901 in large part to advocate passage of federal legislation to do just that.

That milestone legislation, known as the Weeks Act, passed in 1911, and many stakeholders celebrated its 100th anniversary a few years ago. Whereas western national forests could be established by designating lands already owned by the federal government, eastern forestland was in private hands.

Through the Weeks Act, Congress enabled the government to buy lands from willing private landowners to create national forests east of the Mississippi. Congress even appropriated funds to do just that. The first land purchased to become part of the WMNF was acquired in 1914.

The Forest Society’s first President/Forester, Philip Ayres, was a tireless campaigner for protection of and improved management of the White Mountains. He was still at it in 1929, a little more than a decade after the WMNF was officially created, when he penned a kind of status report:

“What are the reasons for the purchase of forest land by the federal government in the East? Purchases are being made continuously throughout the Appalachian Mountains from Maine to Mississippi. The affect the daily life and, to some extent, the future prosperity of all citizens,” Ayres wrote.

Through mid-1929, Ayres reported, Congress had appropriated $19,335,860 with which the government had acquired 3,605,185 acres at an average price of $4.91 an acre. In New Hampshire, 482,848 acres had been acquired by then with another 33,482 in Maine (today the WMNF is approximately 780,000 acres, including 50,000 acres in Maine).

Ayres noted that the acres acquired by 1929 “constitute only about 20 percent of the areas needed…to regulate the flow of navigable streams rising in the Appalachian Mountains. At this rate, the original program adopted in 2011 will be consummated in the year 2010, a record not creditable to the people of the United States.”

He went on to bemoan the fact that in 1900 “when the first plans originated, the total area now contemplated could have been had, it is asserted, for less money than already has been expended on one-fifth of the property.”

Ayres noted later in the piece that “The beginnings of National Forests in the East are likewise a tribute to national intelligence, but action is too slow. It is pusillanimous in proportion to the need. It is our duty and our privilege as American citizens to demand that Congress more speedily provide the East with National Forests adequate to the social and economic needs of its people.”

It’s an old truth about conservation—opportunities to protect critical resources today, while sometimes expensive, will cost far more to protect in the future. And it illustrates the purpose of a national forest—“to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations.”

Or, as famously put by the first Chief of the Forest Service, “to provide the greatest amount of good for the greatest amount of people in the long run.”

Jane Difley, the current President/Forester of the Forest Society (and only the fourth since 1901) provided 21st century perspective on all this at the Museum of the White Mountains celebration when she noted in her comments that the WMNF we have today “reminds us that it’s never too late. We can resurrect a natural resource and protect it when we commit to doing so over the long term.”

Today, the WMNF we know—and shouldn’t take for granted—is absolutely “creditable to the people of the United States”. To see the Museum of the White Mountains exhibit or learn about other talks and events surrounding the 100th anniversary, visit www.plymouth.edu/museum-of-the-white-mountains/.

Jack Savage is the executive editor of Forest Notes magazine, published by the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests. He can be reached at jsavage@forestsociety.org.