- Tags:

- Climate

Looking for Bling: Liz Burakowski prepares to climb a tower and set up an albedometer to measure how much radiation reflects off the forest canopy. Courtesy photo

As a little girl growing up in Wisconsin, Liz Burakowski traveled across the country to visit relatives on the East Coast, passing through toll booths along the way. On the Garden State Parkway in New Jersey, where travelers would encounter a toll booth seemingly every mile or so, Liz was put in charge of keeping track of coins for the tolls.

“Back then kids could ride in the front seat,” she said. “I remember putting a dime and a penny on the dashboard of the car in the sun. My mom would reach for the dime, and I’d tell her to wait, that I was conducting an experiment. The copper penny would get warmer faster than the shiny dime.”

And thus Liz dates her fascination with the “albedo” back to when she was five or six years old.

Albedo? Sounds like a Puerto Rican marinade involving garlic and vinegar. Wait, no, that’s adobo, which helps make pulled pork delicious but has nothing to do with reflectivity. Cuban sandwich, anyone?

Let me think. Albino. Albumen (egg white). Quercus Alba (white oak). Albedo is sometimes described as a “measure of whiteness”. So if according to the latest census New Hampshire is 96 percent white, does that mean our albedo is high?

Oops, off track again. It turns out albedo is “a measure of surface reflectivity, defined as the ratio of reflected energy to incoming solar energy.”

Let’s get back to someone who knows what they’re talking about. Dr. Burakowski, as Liz could call herself if she so desired, is a post-doc working at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, where as a ski and snowboard buff she freely admits to wishing she was back in New Hampshire this winter to enjoy our abundant crop of snow. She got her Masters and PhD from the University of New Hampshire, working with Dr. Cameron Wake, studying the interaction between land cover and climate.

Northern New England is an interesting place to study that relationship. Between the arrival of Europeans in the early 1600s and 1850 the landscape was largely deforested. Over the course of the last 100-150 years our forests have grown back. That has presented an opportunity to try to study the impacts of deforestation and reforestration on albedo over time, and in turn the effects of albedo on climate.

“Trees are pretty dark,” Burakowski explained. “The forest canopy [tops of the trees] absorbs a lot of the sun's energy and re-radiates that as heat.” That means low albedo, which is expressed as a number between 0 (bupkis albedo) and 1.0 (albedo-rama). Right about now an open field near Nashua, for example, exhibits far higher albedo than a dense forest, even though the same amount of snow may have fallen on both.

Ah, I got it: Albedo is Bling. Just like little Liz’s dime. More Bling is cool.

Burakowski’s research indicated that there was likely a cooling effect from the heavy deforestation that peaked in the mid-1800s. Higher albedo meant somewhat cooler temperatures.

I was also interested to learn that the difference between the snow albedo of a mostly deciduous forest (in which the trees drop their leaves in winter) is not that much higher than an evergreen forest; perhaps only ten percent on the 0-1.0 albedo scale.

So does that mean the solution to a warming planet is to cut down all our trees? Not so fast, Burakowski said. Forests provide all manner of economic and ecological benefits, such as sucking up carbon, cleaning our water and air, and providing habitat for our critter companions on this earth.

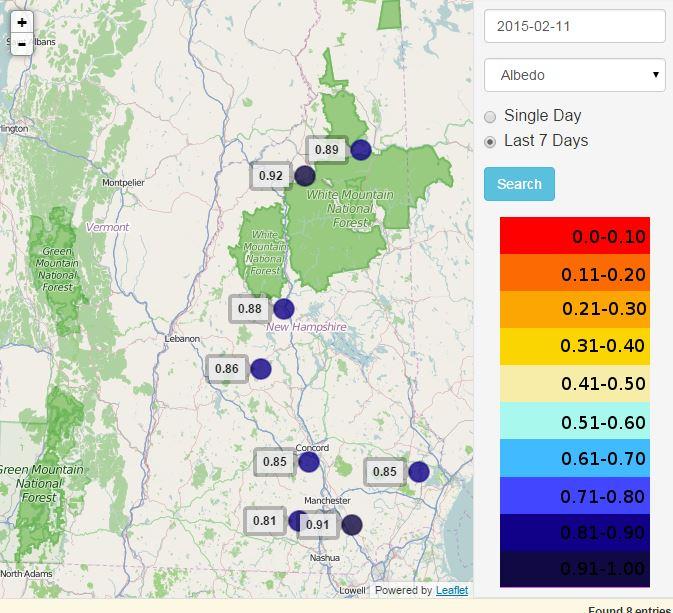

If you want to see the current state of albedo in New Hampshire, check out http://www.cocorahs-albedo.org/map/ , where you can also read more about the research. The map shows reports not only the albedo, but the snow density, snow depth and surface temperature in New Hampshire. No pulled pork recipes, though.

So why do we care about the land-cover Bling factor? Well, as our New England history has already demonstrated, human activity can change our landscape dramatically. And the more we understand how those changes might impact our climate, the better choices we may be able to make. Who knows, maybe there will be big money in albedo farming. Kaching for the snow Bling.

I just want to say one word to you. Just one word. Are you listening?

‘Albedo’.

Jack Savage is the executive editor of Forest Notes, New Hampshire’s Conservation magazine published quarterly by the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests (www.forestsociety.org). Contact him at jsavage@forestsociety.org or follow him on twitter at @JackatSPNHF.