- Tags:

- Clean Water

(Photo: Jerry Monkman)

Since French explorer Samuel de Champlain’s arrival to the Seacoast area in 1605, the Merrimack River has served as a conduit for commerce, recreation, and sustenance for most towns and cities established along its path between Franklin, N.H., and Newburyport, Mass. Prior to colonialism, Indigenous peoples living in the watershed relied on the water course for food and water resources. Today, the Merrimack remains a vital resource in providing drinking water for more than 600,000 people and offering habitats for at least 75 endangered species. So why is this seemingly reliable reserve considered one of most vulnerable rivers by the nonprofit American Rivers as well as the U.S. Forest Service?

The health of our waters first came into focus for him when he was traveling alongside former Senator Edmund Muskie, a key founder of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), as a young reporter for the Portland Press Herald in 1976 during Muskie’s reelection campaign. “He knew pollution,” Hendrickson says. As we are witnessing a new wave of environmental impacts to the river, Hendrickson was inspired to write his book to honor the waterway but also explore opportunities for a stronger future.

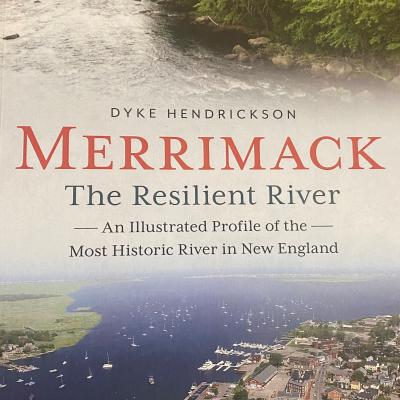

Merrimack: The Resilient River dives deep into the many evolutions of the river, starting with Champlain’s activities and the tragic downfall of Indigenous peoples living in the watershed, to the emergence of textile and paper mills from Franklin down to Lowell, then to the establishment of the U.S. Coast Guard in Newburyport. For Hendrickson, it’s important to ruminate on the past in order to appreciate the river’s value.

“People don’t realize what a remarkable history the Merrimack has and resource it was and still is. Even today when I speak with different audiences, most are unaware of the shipbuilding history and the birthplace of the Coast Guard,” he says. “We have half a million people that don’t understand where their water is coming from let alone the factors that are threatening that source.”

Hendrickson notes that the environmental movement is young compared to the age of the river. In prior centuries, textile mills would regularly dump dyes and chemicals into the Merrimack, turning it different colors and causing an overwhelming depletion of fish populations. As early as 1839, writer Henry David Thoreau was expressing concerns over pollution. In the 1880s, drinking water became an issue in Lawrence with outbreaks of typhoid and other diseases.

In the 1920s, 12 million gallons of sewage was entering the river in Lowell daily. When senators Muskie and George Mitchell helped launch the EPA in 1970 and the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, guidelines were finally established to implement pollution control programs that promoted biological integrity and allowed cities such as Lowell, Manchester, and Haverhill to rebound and become prosperous again.

Nearly 500 million gallons of polluted stormwater and sewage are dumped into the river every year. Additionally, rapid residential and commercial development in southern New Hampshire will only increase the amount of runoff that is already hampering treatment plants in both states. By removing more forests, the opportunity to naturally filter pollutants that harm ecosystems leading into the Gulf of Maine also decreases.

“Contamination, scarcity, and climate change are significant worries when it comes to water,” says Brian Hotz, vice president for land conservation for the Forest Society. “City and town planning is also a complicated issue right now. Municipal planning departments often become siloed in their own work and plan specifically for their town, rather than collaborating across town borders and considering development impacts throughout their whole region,” he notes.

“In the past, we have had to address significant unregulated farm work or bad forestry practices in the White Mountains; now we are mindful of urban development in southern New Hampshire. We are dealing with a lot of rapid development that not only reduces forests but leads to stormwater sewage and runoff.”

While these current realities sound daunting, Hendrickson does not want that to be the key takeaway of his book. “History proves how resilient this river is. By looking back, we can learn from past collaborations and pioneers that rose to the occasion to do the right thing and take the initiative upon ourselves to do better. We had Ellen Swallow Richards, a woman in the nineteenth century no less, help stop typhoid in Lawrence. Muskie and Mitchell crossed party lines to bring environmentalism to the forefront. We have leaders today like Massachusetts State Senator Diana DiZoglio that advocate for infrastructure improvements. Just last year, Manchester committed to a 20-year control plan to alleviate their CSOs due to public input and political involvement.”

In his 23 years with the Forest Society, Hotz says that the Merrimack has always been a key priority with work being done to protect farms, water access, and water quality. This initiative has become more defined over the last decade with the creation of partnership programs, most notably the Merrimack Conservation Partnership.

“We recognized the need for a level of coordination and cooperation by different stakeholders to instill tangible changes,” Hotz says. “Ultimately, land conservation, water quality, and climate change issues need to be viewed in one bucket. By bringing different groups together for routine conversations, these issues are viewed as a continuous lifecycle of processes and people can share ideas and solutions.”

This partnership comprises 30 different groups from Massachusetts and New Hampshire who meet throughout the year to discuss conservation efforts that will have the most significant impacts in protecting the Merrimack. Often individual land trusts and watershed groups advocate and educate in these forums, but they also partner together to enhance or accelerate their work. State and federal agencies participate in these discussions as well, forming a beneficial platform to exchange information, grow efforts, be introduced to new tools, and focus on assets—not deficits.

Along with being involved in partnerships and giving other watershed groups a platform, the Forest Society continues to amplify its efforts to conserve land either through ownership or conservation easements. This includes identifying areas that prevent flooding or provide better farming practices to protect water that is feeding vital systems.

Yet, we do have more involvement from larger regulating groups. Hotz says the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services (DES) is becoming more focused on protecting drinking water and the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) is providing funding for both land conservation and better farming practices to protect drinking water quality. “Many don’t realize the importance of using sophisticated farming techniques and handling nutrients, erosion, and planting appropriately. We are also seeing DES and NRCS work together more often to facilitate restoration work such as pulling culverts and dams and repairing banks to avoid erosion and achieve better waterflows,” he says. Hotz goes on to note that their partnership also led to the Regional Conservation Partnership Program, resulting in a six-million-dollar statewide grant towards further land conservation.

With many factors influencing the largest drinking water source in our state, how is the Forest Society building on this momentum? The summer 2020 release of The Merrimack: River at Risk, a documentary film produced by the Forest Society and directed by Jerry Monkman, has generated new conversations on local and regional levels, and many folks have engaged in river cleanups and the Merrimack Paddle Challenge to view firsthand what is at stake of being lost if the river isn’t protected.

Hotz expresses that there is a concerted effort to ensure that forested areas in the upper reaches of the watershed remain forested. “We are continuing to expand on our work in protecting areas along the main stem of the river above Concord, most notably the Stillhouse Forest in Canterbury and Northfield,” he says. Having purchased around 230 acres in 2019, the Forest Society is seeking to add 76 more acres north of the existing reservation, which would include more than two miles of river frontage. Projects to protect agricultural land also continue with a conservation easement in the works for Morrill Dairy Farm, a 124-acre property in Boscawen that offers opportunities for recreation as well as water and wildlife protection. Facilitating partnerships is another important pillar of the Forest Society’s mission, including maintaining relationships with drinking water suppliers to protect reservoirs such as the Pennichuck and working together with Manchester Water Works, among others.

Hendrickson does have one more suggestion to add to the Forest Society’s to-do list. In researching his book, it was important for him to visit the confluence of the Pemigewasset and Winnipesaukee rivers in Franklin, N.H, where the Merrimack begins. Once he arrived in town, he had difficulty identifying the source and went into a pizza shop to ask where to spot the river’s launch. An employee suggested he go to the far corner of the high school parking lot and lean over a fence line to spot it. After nearly taking a plunge when trying to catch the best view, he feels a proper sign to mark the historic source would be an ideal homage.

For everyone else, Hendrickson’s message is simple: “It is imperative to educate yourself on your surrounding ecosystems, be eco-minded in your daily practices, and speak up to your local officials.”

Brenna Woodman is an avid environmental enthusiast and supporter of the Forest Society. She splits her time between the Seacoast and the White Mountains, where you can often find her (and usually her old rescue dog) at Creek Farm or Bretzfelder Park.