- Tags:

- Wildlife,

- Something Wild

Winter's cold can pose challenges and advantages for wildlife and trees.

This Something Wild episode was first heard in January 2015 and was produced by Andrew Parrella.

Right now the northern hemisphere is tilted away from the sun. Light enters our atmosphere at a much shallower angle and for fewer hours each day. To put it simply, it's cold in New England. And as sure as January's cold the usual grumblings from residents about the plunging mercury abound. It isn’t surprising when you consider how poorly adapted we humans are for living in the cold. However, adaptations in other species in New Hampshire have allowed them to flourish.

How do their feet not freeze off?

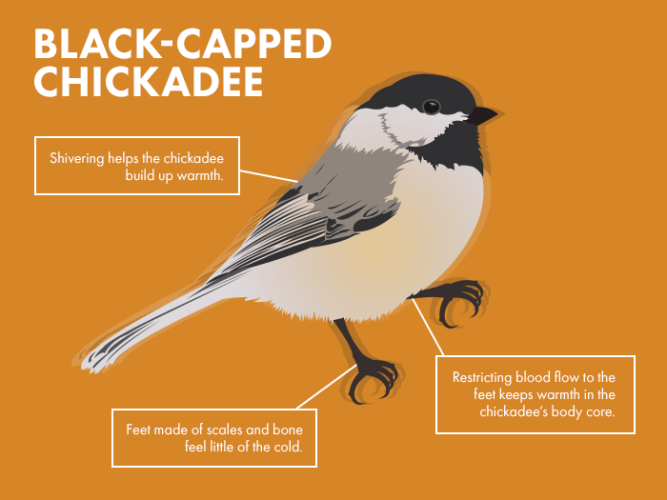

Chickadees, for instance, somehow manage to hang out on snow-covered bird feeders without fear of their feet freezing off. Fact is, their feet are mostly bone and scales, there's very little flesh to develop frost bite or gangrene.

They've also developed a couple of ways to keep the blood where it is needed most. They restrict the blood flow to their feet, which allows them to keep the warm stuff in their core and maintain body temperatures. Shivering is another adaptation these birds have use to protect themselves during the cold winter months. When the sun goes down, they shiver, raise their metabolism, generate a little heat, and then they shut down and get cold. At a certain point, the shivering mechanism kicks on again to generate heat.

These adaptations give an advantage to chickadees and other birds that spend the winter in New Hampshire. They save themselves the rigors they would have spent and dangers they would have had to endure by migrating to points well south of here and back again. Plus, they get an early start on breeding and frequently can have multiple broods while their migrating cousins usually only have enough time for one.

Cold means death for some and salvation for others

Cold means death for some species like the hemlock wooly adelgid, an insect that cannot survive long stretches of cold, which means it has mostly stayed out of New Hampshire. And in turn, the cold is salvation for other species - like the hemlock the adelgid feeds on. The insect is killing hemlocks in milder parts of the country but here in New Hampshire hemlocks have a leg up.

The further north you go the more light-barked trees you'll see.

Bark is an adaptation of trees to cope with the climate. There are trees with light colored bark and trees with dark colored bark. While we warm blooded animals might wear dark clothes to absorb sunlight and stay warm, trees don’t get the same benefits. Dark bark absorbs sunlight, warming up the tree during the day, then temperatures plunge at night. This kind of warming and cooling prompts daily freeze/thaw cycles, resulting in cracks in the bark, exposing trees to all kinds of injuries and infections.

In New Hampshire, we see a lot of birch trees, beech trees - trees with light bark. The further north you go the more of the light-barked trees you’ll see. Farmers apply this principal to apple trees by painting their trunks white, providing protection for the bark of the tree - and next year’s crop of apples!

We hope you'll take some time to appreciate the amazing ways in which life adapts to the cold this winter. And remember warmer weather is sure to return soon, as sure as Something Wild will return next week. In the meantime, keep your bark warm!